A cognitive barrier to longevity planning: valuing the 'now' over the future

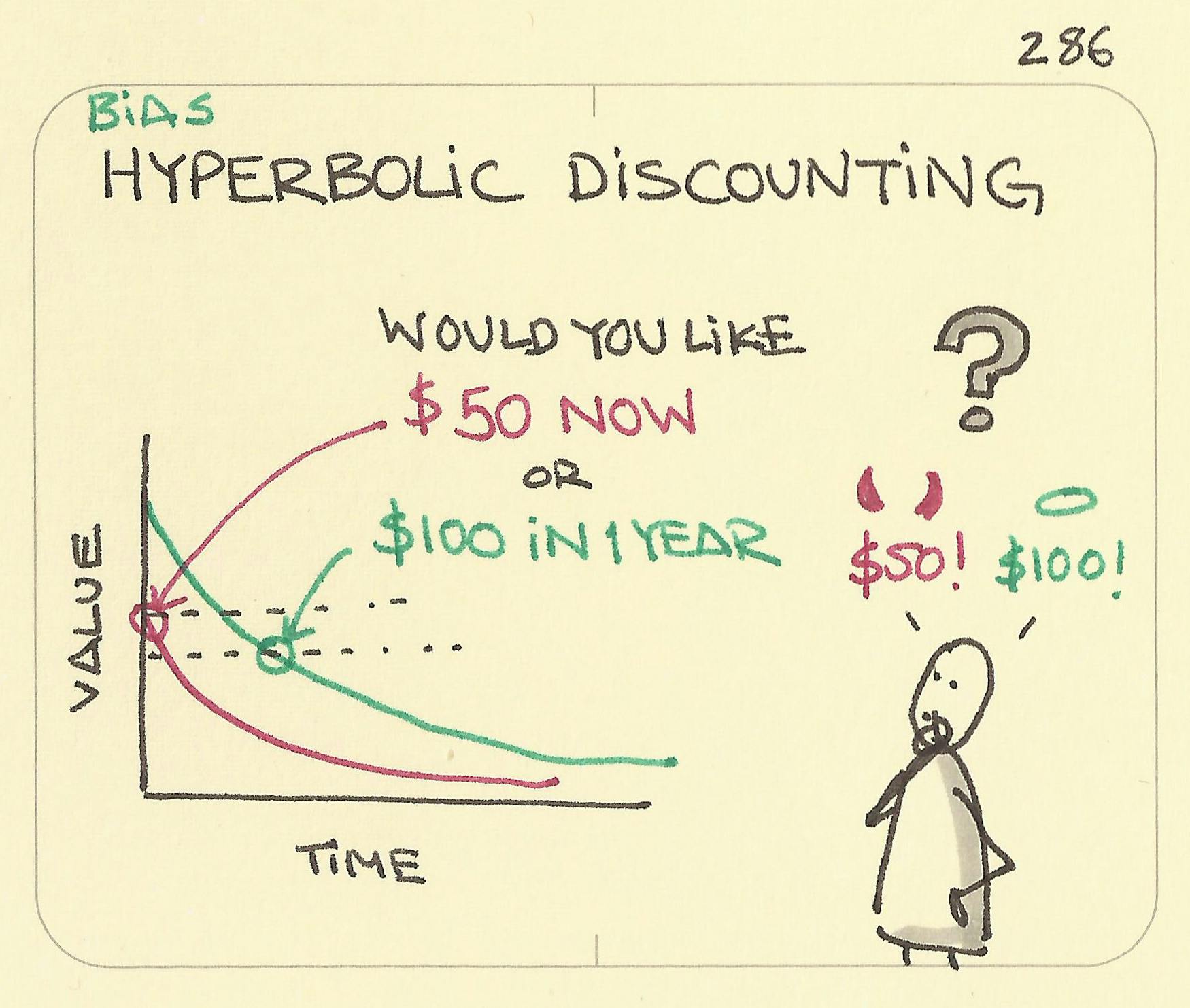

(Banner image from Sketchplanations)

Across the world, people are living longer than ever before. The prevalence of centenarians has nearly doubled in the past two decades. Living to 100 is not the astonishing feat it used to be (although I’d argue it remains quite impressive). The prospect of living longer presents a reason for us to do everything that we can to live better and maintain our quality of life as we age. Accordingly, much of our research here at the AgeLab seeks to explore how we can better prepare ourselves to live well as we age.

Of course, in an ideal world, we would all spend our lives making all of the most sound decisions about the things that will determine the quality of our later life: our finances, our residential arrangements, our social lives, our health.

But we don’t.

One of many reasons we don’t always make the right choices? Hyperbolic discounting.

Hyperbolic discounting is a bias that describes how we tend to value the future less than the present. We go bananas for instant gratification, often opting for immediate rewards over delayed rewards—even if those delayed rewards are much more significant. And this preference for immediate rewards can have a large impact on how we prepare for the future, or engage in what we refer to as “longevity planning.”

We often get our future selves into sticky situations because the priority we place on the “now” leads us to neglect important aspects of longevity planning.

Perhaps one of the most salient examples of the negative implications of this bias involve financial management. We might start off our careers with the idea that we’ll start saving for retirement later (and then later, and then later…), and then either end up being under a lot of stress to catch up later in life or never actually beginning to save. Much of the data from recent research we conducted with Transamerica supports this idea. When we asked survey participants about their savings priorities, younger adults (aged 20-39) were more likely to indicate that they were prioritizing saving for rainy day funds (44.1%), major purchases (29.2%), or vacation or travel (28.7%) than retirement (26.4%). This lack of focus on saving may result in a lot of stress to catch up later in life, as was the case with many of our “midlifers” (aged 40-59)—half of whom were either just getting by or struggling to get by financially. And midlifers were the most likely of any age group to say that they didn’t expect to retire because they won’t have enough money.

I wonder if the “rewards” in hyperbolic discounting can be related to the broader behavior of longevity planning itself. Planning for our future involves more than just checking some boxes; it’s about reckoning with the uncharted territory of our later life, the unknowns that come with unprecedented aging. That can be scary, especially when aging has so many negative connotations on its own. So is it a short-term reward in itself to avoid the feelings of uncertainty, ambiguity, fear that may accompany thoughts about the future; to say, “I’d rather continue to feel good right now, so I’m not going to do anything about this?” When we conducted focus groups as part of the Transamerica research I mentioned above, I recall many people becoming uncomfortable when we asked them about their thoughts about living to 100, or how they were saving for retirement, or what their future life goals were—both near-term and long-term—or really anything about the future. They were much more sure about, and much more willing to dig into, their past and present lives.

It's worth noting that, although hyperbolic discounting bias is most often framed as a “deviation from rationality,” not all decisions that leverage hyperbolic discounting are wrought with irrationality. There are some near-term rewards, like taking money out of one’s savings to cover urgent medical treatments, to pay off certain high-interest debt, or just to take a desperately needed vacation, that just make sense to prioritize over preparing for our later life.

Although it’s tempting to default to whatever is best for the “now,” we would all do well to at least consider the later-life consequences of our big decisions. Our 100-year-old selves will thank us for it.